Missouri Legislature’s Special Session: A Controversial Push for Chiefs and Royals Stadium Funding

Need a quick primer on SB 3? Watch this video. ↑

On June 11, 2025, the Missouri General Assembly concluded its First Extraordinary Session of the 103rd General Assembly, a three-day sprint that culminated in the passage of Senate Substitute No. 2 for Senate Committee Substitute for Senate Bill No. 3 (SS#2 SCS SB 3). The bill, primarily designed to provide economic incentives for new stadiums for the Kansas City Chiefs and Royals, has ignited controversy due to its rushed legislative process, questionable economic merits, potential constitutional violations, and apparent dismissal of public opposition. While the session addressed disaster relief and property tax provisions, critics argue these served as political cover for the stadium deal, with evidence suggesting the property tax measures were never intended to withstand legal scrutiny. Amid warnings from representatives and advocacy groups about constitutional concerns, the bill’s passage has raised questions about lawmakers’ fidelity to their oaths.

The Stadium Deal: The Core of SB 3

SS#2 SCS SB 3 establishes the “Show-Me Sports Investment Act” (Section 100.240), authorizing state funding for athletic and entertainment facility projects for Major League Baseball (MLB) and National Football League (NFL) teams, targeting the Chiefs and Royals. The state can cover up to 50% of construction or renovation costs through annual appropriations, capped at baseline state tax revenues from the facilities, for up to 30 years, and offers up to $50 million per year in tax credits. The estimated $1.5 billion cost to taxpayers over three decades diverts funds from priorities like education, infrastructure, and healthcare and will force cuts in service or increased taxes to address.

The legislation was driven by Kansas’s offer to fund up to 70% of new stadium costs to lure the teams across state lines. Senator Kurtis Gregory, the bill’s sponsor and a former University of Missouri football player, framed it as a matter of Missouri pride, warning against letting Kansas, an “archrival,” “poach” the state’s “pride and joy.”

A Rushed Process and Procedural Irregularities

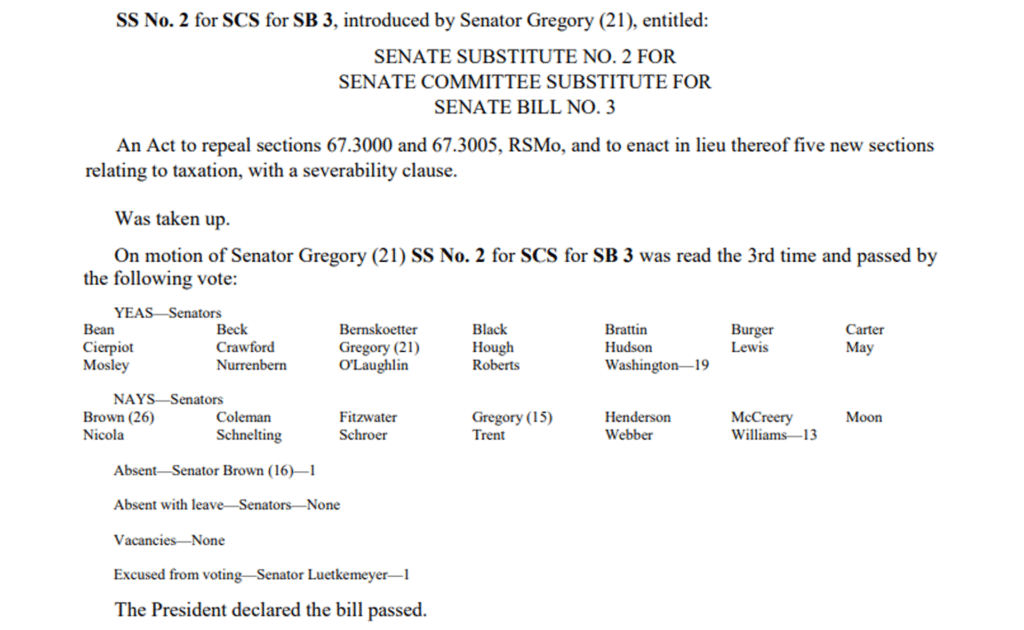

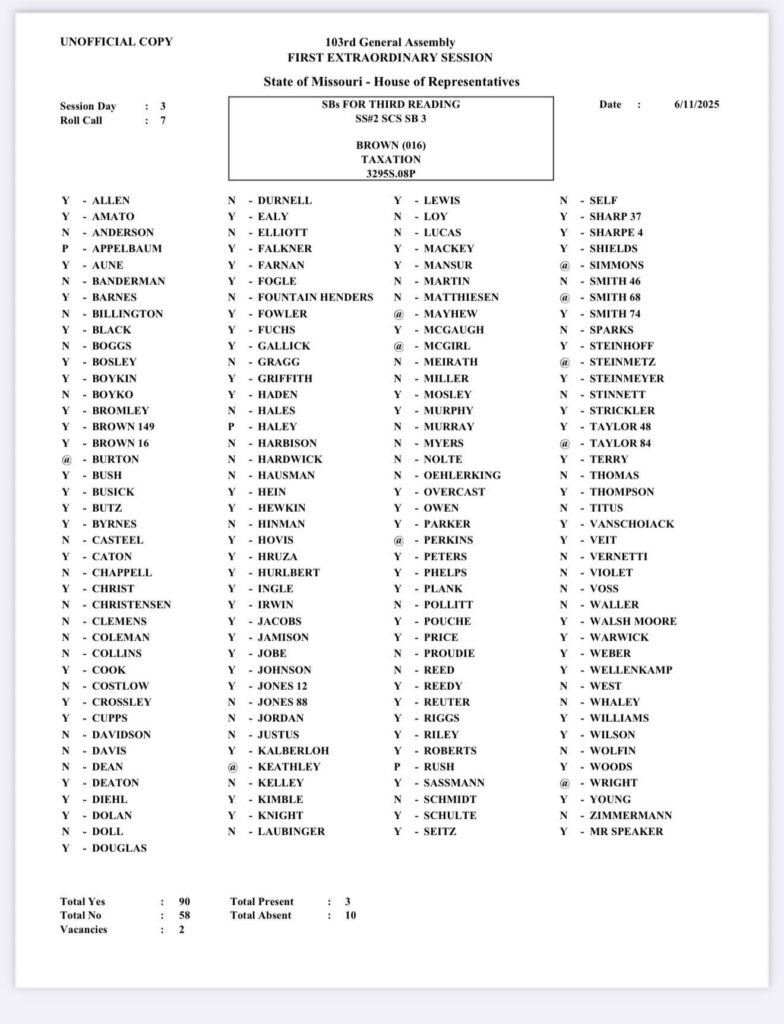

The special session’s rapid pace raised procedural and ethical concerns. The House approved SB 3 by a 90-58 vote on June 11, just days after the Senate passed it 19-13 in the early morning hours of June 5th. Critics argue the bill was rushed without adequate scrutiny, bypassing standard protocols. It was referred to the Economic Development Subcommittee rather than the Ways and Means Committee or the Special Committee on Tax Reform, which typically handle tax legislation. This appears strategic, as members of the latter committees opposed a similar proposal in the 2025 regular session. The Economic Development Subcommittee, with more supporters, voted 11-2 to recommend passage immediately after in-person testimony, before the online testimony window closed.

Who voted for and against?

This move may have violated House Rule 27-A, governing public input. Online testimony, overwhelmingly opposed (172 against, 5 in favor), was seemingly ignored, signaling what critics call “extreme disrespect” for Missouri citizens. The rapid approval limited public engagement and debate, undermining transparency.

Constitutional Concerns and the Severability Clause

SS#2 SCS SB 3 faces potential constitutional challenges, as outlined by the Article III Institute, including violations of single-subject requirements, clear titles, and restrictions on public funds for private benefit. Act for Missouri, during testimony before the Economic Development Subcommittee, highlighted these issues and urged members to pause and consider their oaths to uphold the Missouri Constitution. Representatives Bryant Wolfin, Bill Hardwick, and others echoed this call on the House floor, imploring colleagues to honor their oaths and vote against the bill due to its constitutional flaws.

A severability clause, added at 2 a.m. on June 11 before the Senate vote, intensified concerns. This clause, ensuring that if any part of the bill is deemed invalid, the remainder remains enforceable, is rarely included explicitly, as courts often assume some severability. Its last-minute addition suggests lawmakers anticipated legal challenges, particularly to the property tax provisions (Section 137.1120). Senator Gregory testified that all senators were briefed on the clause, though some dispute their awareness.

The clause appears tied to securing votes from Senators Rick Brattin, Brad Hudson, and Jill Carter, whose support was critical to the Senate’s 19-13 passage. Had two voted no, the bill would have failed. Critics argue the clause reveals the property tax provisions were political cover, expected to be struck down while preserving the stadium funding.

On the House floor, Representative Justin Sparks proposed Amendment 1, which tested this theory by proposing an amendment to replace the severability clause with a non-severability clause, requiring courts to invalidate the entire bill if any part were unconstitutional. Representative Mazzie Christensen urged support, arguing it was the legislature’s duty to address such issues and that a constitutional bill should not fear the change. The amendment failed 90-26, reinforcing perceptions that the property tax provisions were a temporary ploy, designed to be severed, leaving the stadium deal intact. The addition of the severability clause has been criticized as “swamp politics,” placing short-term gains above legislative integrity while rejecting suggestions to change it to a non-severability clause.

Economic Evidence: A Poor Deal for Taxpayers

The economic case for publicly funded stadiums is weak, as noted in analyses by Act for Missouri, the Missouri Independent, and others. Research, including from the Brookings Institution, shows stadiums create few, low-wage, seasonal jobs and shift economic activity rather than generate new revenue. In 2024, Jackson County voters rejected a sales tax for similar stadium plans, reflecting public skepticism. The Chiefs and Royals, valued in the billions, could finance stadiums privately, as seen in Los Angeles, yet Missouri’s plan burdens taxpayers. For every $147,000 spent on stadium jobs, the state could create jobs through other programs for $6,250, highlighting the inefficiency.

Should Missouri Taxpayers Pay for New Sports Stadiums? by Michael Compton

Here’s Why Voters Said No

Read on SubstackDisaster Relief and Property Tax Provisions as Political Cover

SB 3 includes disaster relief measures, such as the Homestead Disaster Tax Credit (Section 135.445), capped at $90 million in FY 2026 and $45 million annually through FY 2055, and property tax credits (Section 137.1120) to limit liability increases in certain counties. Critics argue these were secondary priorities to mask the stadium deal’s intent. The property tax provisions, in particular, appear designed to secure Senate votes, with the severability clause suggesting lawmakers anticipated their invalidation. These measures, while beneficial, were rushed through with minimal discussion, reinforcing perceptions of political cover.

Public Opposition Ignored

The Economic Development Subcommittee’s dismissal of public opposition has fueled accusations of legislative overreach. The 172-5 online testimony ratio against SB 3 echoes the 2024 Jackson County vote. Many Missourians believe the Chiefs and Royals are unlikely to leave Kansas City due to their fanbase and history, viewing relocation threats as a tactic to extract public funds. Social media on platforms like X calls these threats a “bluff,” urging prioritization of public welfare.

Conclusion: A Betrayal of Oaths

The Missouri Legislature’s special session has left a tarnished legacy. Despite warnings from Act for Missouri and Representatives Wolfin, Hardwick, and others to uphold their constitutional oaths, the 90 House members and 19 senators who voted for SS#2 SCS SB 3 ignored glaring constitutional flaws, economic evidence, and overwhelming public opposition. The rushed passage, strategic committee assignment, and last-minute severability clause reveal a calculated effort to use disposable property tax provisions as political cover for a $1.5 billion stadium deal benefiting billionaire team owners. By prioritizing civic pride and political expediency over their sworn duty to the Missouri Constitution, these legislators have eroded public trust. As the bill awaits Governor Mike Kehoe’s signature, Missourians are left questioning whether anyone in Jefferson City has their best interests in mind or if only the Lobbyist class is heard.